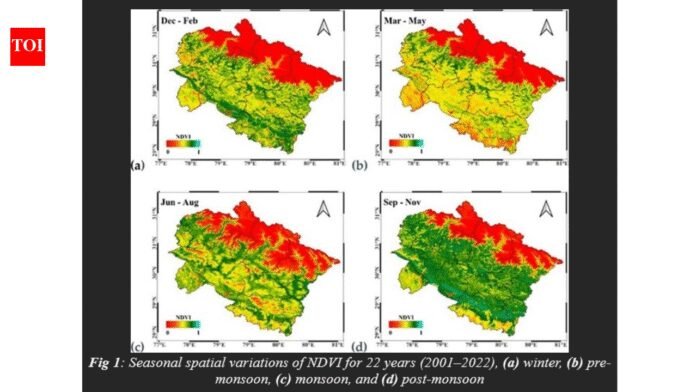

BENGALURU: Satellites watching the sweep of the Himalayas have begun to read the mountains like a slow-moving diary. Grasslands revive with the seasons, forests deepen in colour, and valley flora shifts its pattern, yet the same images also carry warnings of strain. An analysis of two-decade data of Uttarakhand’s vegetation shows how closely the region responds to climate and how those rhythms are starting to falter.Mountain ecosystems react faster than most landscapes to changes in temperature and rainfall. Rising global surface temperatures and altered precipitation patterns are already influencing plant growth, soil moisture, and snow cover. Scientists say this makes local and long-term monitoring essential if govts are to prepare for floods, droughts, and biodiversity loss.To track these changes, researchers from the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) in Nainital, an autonomous institute under the department of science and technology (DST), worked with Indian and international collaborators using Google Earth Engine, or GEE, a platform that processes large volumes of satellite data. The tool allows scientists to study land degradation, urban growth, dust movement, and temperature trends without the heavy burden of storing raw images.The team examined satellite records from 2001 to 2022 and relied on a widely used indicator called the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). The index measures how plants reflect light and provides a simple guide to their health. Low NDVI values point to rock, sand, water, or snow, while higher values signal dense forests, croplands, or wetlands. The researchers also studied the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), which performs better in areas with thick biomass.Their findings of the study led by Umesh Dumka from ARIES, published in the journal “Environmental Monitoring and Assessment”, reveal clear seasonal cycles. NDVI and EVI peak after the monsoon when hills turn lush, and fall to their lowest levels before the rains. Monthly and yearly variations follow a familiar pattern, yet the long-term graphs show a gradual decline.The study links this drop to deforestation, expanding agriculture, illegal logging, and rising pollution from towns and industries. Pollution, the researchers note, does not strike evenly. Some pockets suffer heavier damage, adding to the stress created by warming temperatures and erratic rainfall. Such pressures threaten wildlife habitats, river systems, and the livelihoods of millions who depend on the mountains downstream.Using time-series maps generated through GEE, the scientists compared vegetation trends with climate data and applied Pearson’s correlation to understand their relationship. The approach allowed them to pinpoint districts where greenery has weakened most sharply.The authors argue that satellite science can serve as an early-warning system. By identifying vulnerable zones, authorities can plan afforestation, regulate construction, and control emissions before losses become irreversible. The Himalayas, they say, are signalling distress in a language of pixels and numbers. Listening to that message may decide how resilient the region remains in the decades ahead.